Why Learning Mandarin Did Not Fit My Ethnic Identity

In Malaysia, our ethnicity is recorded on so many official documents—identity cards, school registrations, even membership cards. The categories are oversimplified into Malay, Chinese, Indian, and Other. It all seemed so straightforward until I had the chance to dive into a cultural exchange during my Master’s degree. That two-year adventure was both overwhelming and enlightening.

Challenging Ethnic Labels and Mixed Marriages

I always considered myself ethnically Chinese by default. Peranakan, a term for the descendants of Chinese immigrants who married local Malays, wasn’t an option for me. My grandfather even inquired at the government department about changing our classification, but he came back disappointed. I also wondered about children from mixed marriages: what ethnicity are they assigned?

I learned that if a child from such a marriage is born without a marriage certificate, they inherit the mother’s ethnicity; if there is a certificate, they inherit the father’s. Imagine a child from a Chinese-Indian marriage who might look different from other “Chinese” children—darker skin, perhaps. This could make them feel isolated or excluded.

I regret learning mandarin

Reflecting on my own experience, I regret learning Mandarin. At one point, I truly believed Mandarin was my mother tongue. We were taught that Hokkien is just a dialect of Chinese, where “Chinese” meant Mandarin. Recently, I discovered that Hokkien and Cantonese actually stem from Middle Chinese, while Mandarin belongs to a different branch. This revelation made me question why I had accepted Hokkien as a mere dialect. Is it because Hokkien lacks a standardized written system?

The more I explored these linguistic nuances, the more I realized how language can be influenced by political and social factors. Language ideologies are not neutral; they reflect and reinforce cultural and political narratives. The perception of Hokkien as merely a dialect of Mandarin is a product of these ideologies, often ignoring its rich historical and cultural significance. Historically, countries like Japan, Korea, and Vietnam adapted Chinese characters into their own scripts. Cantonese uses Chinese characters, but with different sounds and meanings compared to Mandarin. Hokkien, too, uses Chinese characters, but its pronunciation differs significantly.

Japanese Kanji and Its Unique Context

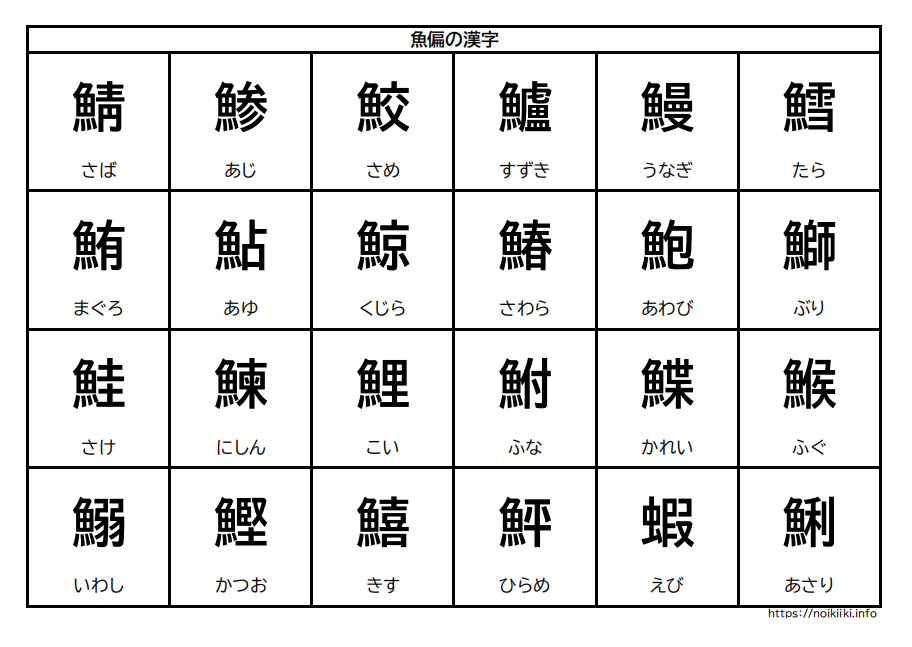

To illustrate this point, consider the image below.

It shows a Japanese kanji that doesn’t exist in Chinese. This kanji, with its radical of fish, highlights how different cultures have adapted and evolved their writing systems based on unique linguistic and cultural needs. Just as this kanji is specific to Japanese, the ways in which languages and ethnicities are classified and perceived can be deeply influenced by political and cultural contexts. This realization—about how languages evolve and are influenced by cultural and political contexts—made me rethink my understanding of Mandarin and Hokkien.

Shattered and Reformed

This entire journey has led me to a place of confusion regarding my own ethnic identity. I find myself questioning whether I should identify with the Baba-Nyonya culture, or if I am merely trapped by the rigid ethnic labels that dominate official documents in Malaysia. While I don’t fully self-identify as Baba-Nyonya, I’m increasingly aware that these ethnic labels do not capture the complexities of individual identity. Instead of fitting neatly into these categories, I now see them as limiting constructs that often fail to represent the richness of our cultural backgrounds.

It’s a reminder to myself that language is not just about communication but also about identity and politics. In a linguistic context, languages that are not mutually intelligible should be recognized as distinct languages. However, these languages are often categorized as dialects of a dominant language. I wish we had been taught that Mandarin serves as a lingua franca for Hokkien, Cantonese, Hakka, and other speakers in Malaysia, rather than as the sole representation of “Chinese”. It saddens me that I forgot my true mother tongue is Hokkien and that so few recognize it as a distinct language.